A Reason to Go Somewhere That Might Not Have Occurred to You

Bryan Stevenson is a very quiet revolutionary. His career until recently was very much “on the ground.” He worked as a lawyer and advocate among those people whose race, class and the circumstances of their lives had disadvantaged them in the world. It was good work to do and he did it well. He won a MacArthur in 1995 and he gave a groundbreaking TED talk. But what is remarkable is that at the absolute summit of his career he made a move that was truly revolutionary: he looked to the past and made something.

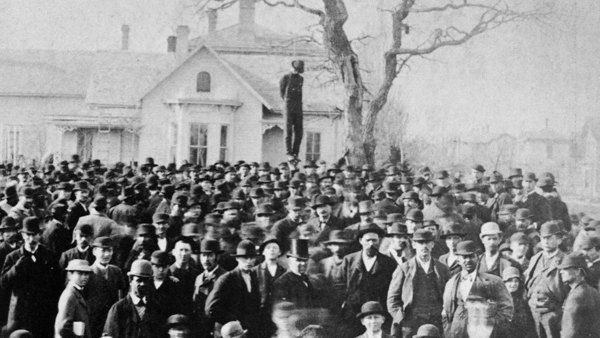

The something he made is in Montgomery, Alabama––a city that might not be on many peoples' travel itinerary. What Stevenson built there is a memorial to the more than 4,000 African Americans who were lynched in the Southern and Western states from 1877–1950. There can't be a more disappeared group of victims in the world than these men and women who, under the oppression of Jim Crow, were accused, captured, and killed by mobs of white people who took out their ire by hanging black bodies from trees in every Southern state. It is an unimaginably grotesque part of our history as Americans that is largely scrubbed from historical accounts of the period as they are shared in official histories, like those shared in public schools and in museum exhibits.

These accounts are so scrubbed that the narrative itself is a huge part of what Stevenson made. Putting together this monument entailed years and years of careful historical work that entailed looking through spotty records, newspaper clippings and extraordinary historical sources to discover these often unnamed victims of mob violence and hatred and the complicity of state power. But, if that work wasn't enough, there is––especially of interest for the readership of ManMade––the monument itself. Stevenson and his collaborators built a memorial of 805 steel plates that hang from the ceiling, representing the 805 counties where these lynchings occurred. It is an extraordinary piece of art that perfectly encapsulates the purpose of the monument. And it is a project that––I can only imagine––took as much ingenuity and care as it did seriousness of purpose.

Here's a bit more from their website:

The Memorial for Peace and Justice was conceived with the hope of creating a sober, meaningful site where people can gather and reflect on America’s history of racial inequality…Set on a six-acre site, the memorial uses sculpture, art, and design to contextualize racial terror….The memorial structure on the center of the site is constructed of over 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns.

The memorial is more than a static monument. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not.

Montgomery, Alabama has never been on my list of places I must go. But I'm pretty sure I need to go to this place and be confronted by a history that shapes the nation in which I live. I need to see the coffin-shaped metalwork and steel beams and struts that makes manifest the work of retrieval and that Stevenson and his partners have done. For the sake of people who have spent decades unseen and unacknowledged, I now have a reason to go to Montgomery.

Learn more about the National Memorial for Peace and Justice at EJI.org