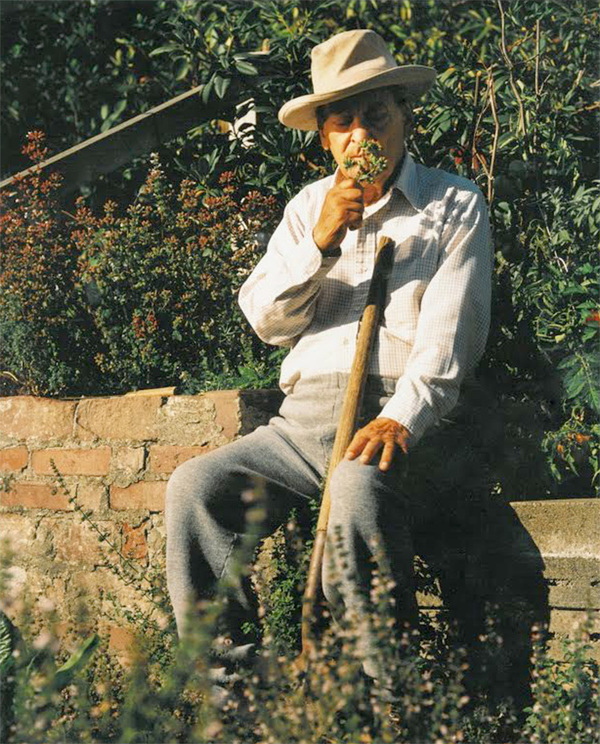

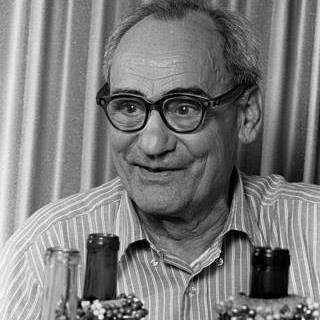

Meet Angelo Pellegrini, the Original Maker Almost No One Knows About, but Totally Should.

You can barely imagine what the world was like in the proto-suburbs of the Pacific Northwest for a child who had traveled there––entirely on his own, with his mother at home and his father awaiting him––from a small Tuscan village. This was before “a small Tuscan village” was even a thing on the radar of America at large. And it was before America had its culturally and politically dominating century. It was before anyone knew what the Pacific Northwest would become, foodwise.

And yet, that is where Angelo Pellegrini settled. His childhood of 12 or so years in Tuscany gave him an uncanny experience to bring to pre-depression America, including an adult life that coincided with the Cold War in which his heritage could not have been less relevant. He was born at just the right time to enjoy America in a way that few others had. But he was also born just a bit too early to have been the celebrity he would have been if he had emerged in the age of Alice Waters and the Food Network.

His mantra was to grow (or forage) your own produce, cook your own food and make your own wine. And he did all of this unironically because it had been baked into his bones to do so. Unlike every food writer you (or I) have ever read, Pellegrini drips with a kind of authenticity and nativism when it comes to procuring and making food that feels somehow deeply of the old world and yet also completely American. He should be beloved by all. Instead, he is hardly read. That should change.

Here are some of the amazing things about Pellegrini.

He may have been one of the first people to publish recipes for pesto and minestrone. He arrived at Ellis Island at the age of 10. Only a few years later he was teaching English Literature at Washington State University. As a child in Tuscany he competed with village children to find things to forage from the forest and fought over access to manure that he could eventually sell to farmers. As a child in America he found untouched forests and boundless plenitude and could not understand how people could leave fallen trees and then pay for firewood. He avoided American food––except for ham and eggs––throughout his life not because of fear or cultural judgment. He simply didn't find it delicious. And as a deeply touched boy from the foothills of Florence, food that was not delicious was not worth eating!

His books are astounding in their scope, their insightful bearing, and their readability. The only one still in print (as far as I can tell) is The Unprejudiced Palate––part of a Modern Library series on cooking from the 20th century. But it originally appeared in 1948. Can you imagine? WWII was only 3 years in the past. England was still in the midst of a food crisis and rationing that would continue for a decade. Pellegrini was writing about the leisure of the garden and the importance of a wooden winepress. His other deeply informative book is The Food Lover's Garden. You can buy it used. And you should. He talks about gardening not as a process of turning part of your yard into something useful. He describes a way of life. It is full of very specific instructions, but you can also read it like a novel, turning it page by page as you get through it.

Finally, there is the almost revolutionary Lean Years, Happy Years in which he appeals to his own way of life––lived frugally by instinct––and in the process indicts an entire culture of American excess. And to me, this is always what makes him most important. He is not outright political, but he ascribes to an ethics that necessitates a political philosophy that is at odds with how most people live their lives. He talks about golf courses and their verdant, land-swallowing hills. He doesn't come out and say “what a waste of space”––though given his impoverished background, you can imagine what he thinks. Instead what he says is, “they are a terrific spot to forage for mushrooms, and you should because no one else thinks to do this!” He alludes to the abuse he received as a non-English speaking child, but does not focus on the brutality he suffered. Instead he points out that his abusers would throw away the crusts of their sandwiches, as if that showed what poor, unenlightened souls they really were. He is not an atheist, but talks reverently of his father and his habit to forego church and, instead, to hunt for rabbits early in the morning in order to prepare them for Sunday dinner. Over the course of a page, he describes a “communion table” in which his father would carefully clean the innards of the rabbits in order to make an omelet.

There is so much in Pellegrini to love and adore. And yet his notoriety and fame are regional at best. Even in the age of digital publishing, his writing goes unread. I think there is a great tragedy in that, because in all of our attempt to rediscover the crafts and creating habits of an old world, his is a voice that really can bring that past into our present.